Traders, guardians and big data

698 words | ~3 min

I find it amazing that people can talk seriously about the idea that big data might spell the end of theory. After a decade in which data analysis failed to provide a credible risk model for the global financial system, you'd think we'd be a bit more circumspect about off-model risk.

But then I'm a strategist by inclination, so I would say that, wouldn't I? I tend to believe that analysis of the available data should be balanced with thought, imagination, speculation. Rather than prolonging the argument, it's worth looking at why certain claims are made about big data, and what they tell us about the competing visions of the future that they represent.

The emerging field of big data is an odd cultural mix at the moment, like the world of high finance was in the 1990s. It has put C.P. Snow's two cultures - in this case, advertising and technology - in the same room to see what happens. As we've seen, that can be a productive but very unstable mix. We need a way to spot each others' assumptions - and our own.

I'm grateful to Andrew Curry for introducing me to Jane Jacobs' model of Traders and Guardians, from her book Systems of Survival. It offers a nice way of thinking about how different mindsets approach the problem of progress (social, technological, etc.). I quote from Mary Ann Glendon's reviewof the book:

Because traders’ prosperity depends on making reliable deals, they set great store by policies that tend to create or reinforce honesty and trust: respect contracts; come to voluntary agreements; shun force; be tolerant and courteous; collaborate easily with strangers. Because producers for trade thrive on improved products and methods they also value inventiveness, and attitudes that foster creativity, such as "dissent for the sake of the task"...

Guardians prize such qualities as discipline, obedience, prowess, respect for tradition and hierarchy, show of strength, ostentation, largesse, and "deception for the sake of the task." The bedrock of guardian systems is loyalty. It not only promotes their common objectives, but it keeps them from preying on one another. They are wary of, even hostile to, trade, for the reason that loyalty and secrets of the group must not be for sale.

Guardians and traders fulfil different roles. Guardians give continuity, protection, standards, quality. Traders give disruption, innovation, growth, opportunity. According to Jacobs, problems arise when the two systems of behaviour get mixed up or imbalanced. When you have too many traders, you end up with the kind of overconfidence that generates instability and risk. When you have too many guardians, you end up with the kind of overconfidence that generates complacency and stagnation.

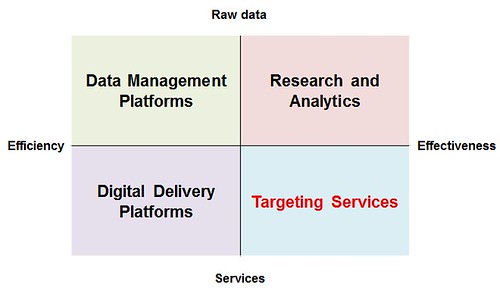

Big data contains plenty of traders - doing deals, chasing the new new thing. But also plenty of guardians - applying models and processes, promoting standards and best practice. The two need to be kept in balance. Too many traders and we'll end up selling way ahead of our capabilities, cutting corners, disregarding expectations of privacy. Too many guardians and we'll build white elephants that don't move with the times.

Traders tend to incline to the view that big data will kill theory - like all the other 'this changes everything' tech and financial fads of the last twenty years. They stand to be disappointed. Guardians tend to think it won't, that it's a useful accelerator of traditional research and analysis techniques. Both are likely to be surprised, and both need to pay close attention to the other's point of view.

If the guardians win the day, big data will stagnate into a world of heavy-duty IT platforms. If the traders win, we'll find ourselves in a bubble that may burst with damaging consequences. If the two learn to balance each others' demands, they might create something of lasting value.

# Alex Steer (14/04/2013)