Why tech companies are killing agencies, and vice versa

1026 words | ~5 min

Once upon a time, there were full-service ad agencies. They didn't call themselves that, of course. They just called themselves ad agencies. But they did all sorts of things like media and research, as well as creative work.

Then one day - okay, one decade - they gave away those 'marketing services' functions. Media and market research went off to become entirely separate industries. The creative agency function remained boutique and special. Media and research went off and chased scale and efficiency.

At around that time, the people who did marketing realised that the web was going to be a bit useful, maybe. And the kids who made stuff for the internet realised that marketers would pay them. The kids set up their own companies to build internet stuff for marketers, and the marketers - who were getting used to paying separate agencies to do creative, media and research - were more or less happy to ad these 'digital' agencies to their lists. They never expected the internet kids to join ad agencies.

So we ended up with a world in which marketing services companies and creative agencies found themselves competing for the time, attention and love of marketers. For a long time creative agencies got most of the love - they did powerful, beautiful, interesting work; the marketing services firms were the useful, efficient drudges. As for the internet kids, they occupied an odd middle ground. Some looked more like marketing services firms, others acted more like ad agencies. Anyway, we broadly ended up with two cultures: one tidy, scalable and efficient; one elegant, interesting, deeply connected to what people were thinking and feeling.

I think we all know how this fairy tale ends.

One day, the economy fell apart. Marketers tended to look at the slightly devil-may-care attitudes of the agencies and got a bit nervous. Big bets, leaps of faith... these things started to look dangerous rather than daring. Over on the other side, the media and research firms were testing, measuring, proving. That suddenly looked a lot more appealing.

So the marketing services people started to take the upper hand - more love, more attention, more say in how money was spent. The agencies found themselves backed into a trendily-designed corner. And as this happened, the marketing services firms realised they had a secret weapon.

The internet kids, stuck in the middle.

Technology and data could make things more robust, more measurable, easier to prove and improve. And in the meantime, the internet kids had grown up. The ones who hadn't been acting like agencies had got suits and a bit of money. They'd become technology consulting firms, and some of them had been absorbed into the big professional services firms who had moved a bit faster than some of the marketing services guys.

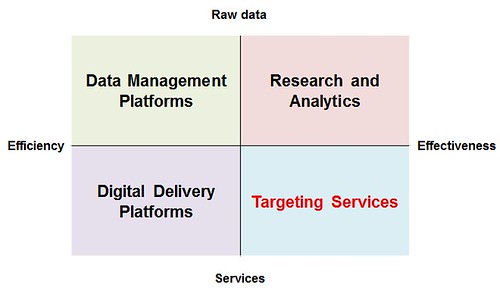

So the marketing services firms started doing deals, partnering with the tech consultancies, and hiring people in. After a while the line between media companies and technology companies (and even to some extent research companies) began to blur. Media became technology-driven. But more than that, it became highly technical, full of really good models of what worked, and some really smart ways of building pictures of the audiences for marketing: who they were, where they want, what they did, what they liked.

And here we are. The marketers are spending a lot of time talking to the marketing services firms (the media guys, the tech guys, the research guys), because those guys talk sense. As for the agencies, they've hired enough of the internet kids that they can talk a good game about social media and built some whizzy applications that other agencies love. But it all still feels a little bit... precious.

Not surprising, then, that you hear a lot of people saying that the marketing services firms have won the battle for love and attention. They've got the money, the evidence, the scale, the buzz...

Just one problem with that story.

The agencies still understand how to move people. And the marketing services firms don't.

If you're a marketer, the experience of working with marketing services firms on consumer marketing problems is, by and large, horrific. They've got the tech, the metrics, the models, the smarts, the money... But do one in a hundred of them have the sheer creative problem-solving ability that you need to build a strong brand, change a perception, change a behaviour?

The agencies still have it, and have it in spades. The best planners, the best creatives, are still in agencies, creating ideas that motivate people and drive growth.

And that means agencies can still win.

That's 'can', not 'will'. In the short term there's a very good chance that agencies will lose. If they keep ignoring technology, they'll lose. If they keep playing fast and loose with data, they'll lose. If they keep only using the web to be interesting and fancy, without finding ways to become the experts in what kinds of digital activity drive changes in behaviour, they'll lose. And if the marketing services firms invest hard in creating environments that smart strategists and brilliant creatives can do great work in, the stand-alone creative agency model is dead.

But that hasn't happened yet, whatever the promotional literature says. So if agencies become the experts in effectiveness again, they'll win. If they become serious strategic business partners for their clients, they'll win. If they become the specialists in building the right technology and media mix to generate change and growth, not just reach and frequency, they'll win.

The winners will be the businesses where the smartest people want to work, proving they're solving the most interesting problems in the most powerful ways. Those people will be writers, artists, editors, designers, strategists, project managers, engineers, statisticians, planners, buyers, researchers... Together. Because I don't believe marketers want to spend their time persuading different types of people to work together without fighting. They want organisations that care about relationships and results in equal measure.

Less pitching. Less bitching. More work.

# Alex Steer (23/02/2013)