Time to take privacy seriously - part 1

1705 words | ~9 min

The stakes have been raised in the online privacy debate again. The White House recently announced plans for a data privacy bill of rights, which together with the EU's data protection reforms mean that it will be increasingly difficult to collect behavioural data from internet users without their consent. It's increasingly likely that the law will require users to opt in before their online behaviours can be tracked, stored and used for targeting.

When issues start to reach the attention of high-level policymakers, it's usually a sign that their time has come. Another sign of the times is the sudden appearance of pieces on online behavioural targeting in the business press. To their credit, the Wall Street Journal have been running with this for the last couple of years with their excellent What They Know site. But they're now being joined by a wave of other voices, including Jerry Michalski's in his piece for Forbes from a few days back, Big Data and the Stalker Economy:

Big data is strategic now. Facebook is valued at around $100 billion because it has collected a treasure trove of data that may unlock the secrets of selling more things to more people. Most other companies would like to have whatever they’re having. Google offers free email, word processing, mapping, analytics, video, videoconferencing and much more because they’re selling us to advertisers. The byword these days is, “if you’re not paying for the service, you’re the product.”

Not all commentators are as even-handed as Michalski. Expect to see a lot more pieces over the next few months like this one from Molly Wood at CNET, which takes data mining far more personally, and conjures up a cast of 'shadowy data brokers slurping up every last byte about you'.

As Victor Hugo put it (only in French), nothing is more powerful than an idea whose time has come.

It's time for those of us who work in the marketing technology industry to get serious about data, privacy and permissions.

Data panic: a history

Let's get this out in the open. I'm one of those shadowy data brokers (apparently). I work in digital marketing, in a part of the industry that relies heavily on using information about people's online behaviour to help organisations make decisions and respond to their customers faster, more efficiently, and (I hope) more effectively too.

So what does that mean? It means I absolutely have a stake in this game. So if you're looking for an entirely even-handed commentary you might not come to me first. But it also means I understand a lot of the uses of this kind of information, I know what gets collected and what doesn't, and I know some of the range of attitudes to people's data that exist within the industry. The problem with a lot of the commentary we're seeing it's that it's classic 'first draft of history' stuff - timely, urgent, powerful, but not always well informed. Of course, you don't just want to rely on experts when evaluating the social impact of a new technology. Experts, by definition, are always implicated, often very close to their subject, and can find it hard to step back. But when a debate's important (and I think this one is), it's important to scale up the expertise of non-specialists as quickly as possible, so that the debate is informed as well as lively.

For what it's worth, I'm more of a scaled-up non-specialist than an expert. As readers of this blog will know, my background's not in data science and analytics but in advertising, strategic planning and futures with a technology angle. My current interests are in helping clients make the best use of all this information, rather than in the complexities of statistics or modelling.

I'm close enough to my subject, though, to know that we're going through a period of what I call 'data panic' at the moment. If you know where to look, you can chart its mainstream evolution back over a period of about five or six years. Here are what I think are some of its important stages so far in the US and Europe (where it's most prevalent):

- Several high profile public-sector data leaks (including this one in 2007, and endless stories about civil servants leaving laptops on trains) provide easy headlines in the classic 'incompetent public management' mould we know and love. They also start to highlight the scale of data collection by the state, and the lack of training and safeguards associated. A few similar leaks in the private sector hit headlines, including the huge leak of AOL search data in 2006.

- Around 2009/10, the scale of social network use got impressive enough that social phenomena became observable. One of these was the possibility of embarrassment (or indeed unemployment) arising from your drunken photos turning up in front of your parents/loved ones/prospective employers.

- The public-sector data leaks (point 1) lead to growing pressure against the expansion of public-sector data collection, and concern about proposals to join together existing databases held by different public bodies. The scrapping of the UK's ContactPoint database of children's personal information in 2010 is a case in point. At this stage, there is still little scrutiny of, or interest in, data collection by the private sector.

- Not until about late 2010/early 2011 does private-sector data become a hot topic. It starts, in the UK at least, with the kinds of loyalty card data that major retailers keep on their customers. Brands like Tesco become early targets for scrutiny.

- At around the same time, social networks (especially Facebook) are really hitting their stride and coverage is starting to focus on the downside of their enormous popularity. Much of the early conversation is around the idea of 'context collisions' - as coined by BT's Bruce Schneier, mentioned in point 2 above - and the idea that parts of your life that were previously separate are forced together online. (This insight drove the development of Google Plus's 'Circles'.) But the scale of the issue starts to get attention too. That means journalists and analysts start looking not just at individual scare stories, but at the business models of social networks which depend heavily on collecting data, and often seem to make their privacy settings complex, hidden, and very open by default.

- We come full circle with some high-profile data leaks and hacks - but this time with the focus on the private sector. Headline events like the Playstation Network hack and the Epsilon email marketing database reinforce the idea that personal data is both widespread and fragile.

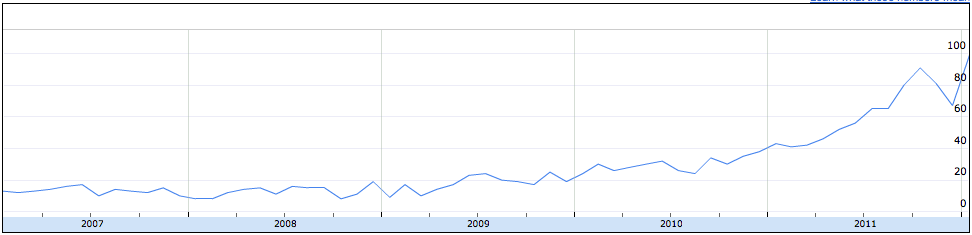

- Last but not least, as 2011 drew to a close, came a renewed focus on the unnoticed scale of online behavioural tracking. The WSJ, as noted, had run with this one for a while, but stories like the iPhone location file and Android keylogging gave it further momentum.

There are two strands to the story above. The first is surprising scale and the second is surprising exposure. As the two storylines have progressed over the last few years, the public has been left with the sense that more of their personal data is out there than they realised, and that it's in the hands of people who can't necessarily be trusted with it.

Now, as we move into 2012, let's throw another element into the mix: advertising. Let's face it, lots of us find the idea of advertising (as distinct from individual adverts) either boring, or patronising, or disturbing, or all three. Few of us like to think our attitudes - or behaviours - are influenced by the ads we see, and we don't want to volunteer to see more of the humdrum hard-sell that the A-word conjures up in our minds.

So there's a perception that we now live in a world in which the people who make ads are secretly tracking our every move, piling up our private data and selling it to each other... so they can show us more ads. This perception gets confirmed by those stories (which are now primed to hit headlines and be shared in a climate of real concern) in which the scale of data, the risk of exposure and the annoyingness of advertising come together in a perfect storm - like the recent one in which Target identified that a young woman was pregnant from her purchasing behaviour, before her father knew.

It feels intrusive and dangerous and underhand and wrong. And that's the context in which legislators are under pressure to make changes.

The next post in this series will deal with the short- and long-term risks of the current privacy environment, some likely developments in legislation and in public perceptions of data, and the need for some realism and honesty from marketers.

# Alex Steer (11/03/2012)